Zimodem Escape Sequence Fix

Last updated: Sep 17, 2020

Back in the 1980ies and before the Internet existed, the popular way to go online were Bulletin Board Systems (BBS). Typically, these were home or personal computers owned by individuals and hooked up to a telephone line through a modem. They ran some custom-made or later off-the-shelf software providing functions like email, newsgroups, file transfer and chat. Usually, they provided a club-like atmosphere with a small group of people calling in every day, exchanging news, gossip and files and ocasionally chatting with the operator of the BBS.

I was a BBS user for a year until I discovered the UseNet and BITNET. These networks provided BBS-like functionality, but on a global scale. The audience still was somewhat small with an overall user population in the ten thousands, but things were growing quickly and eventually, the Internet mostly took over all these predecessor systems.

BBSing today

Mostly, because BBSes never really died. They migrated into the Internet, so instead of using a phone line to connect, you’d use telnet or ssh. Being club-like, integrated environments with a small user base still had its appeal to a number of BBS users. Some the systems lived on till today, some former phone based BBSes reopened years later in the Internet and some new ones just popped up.

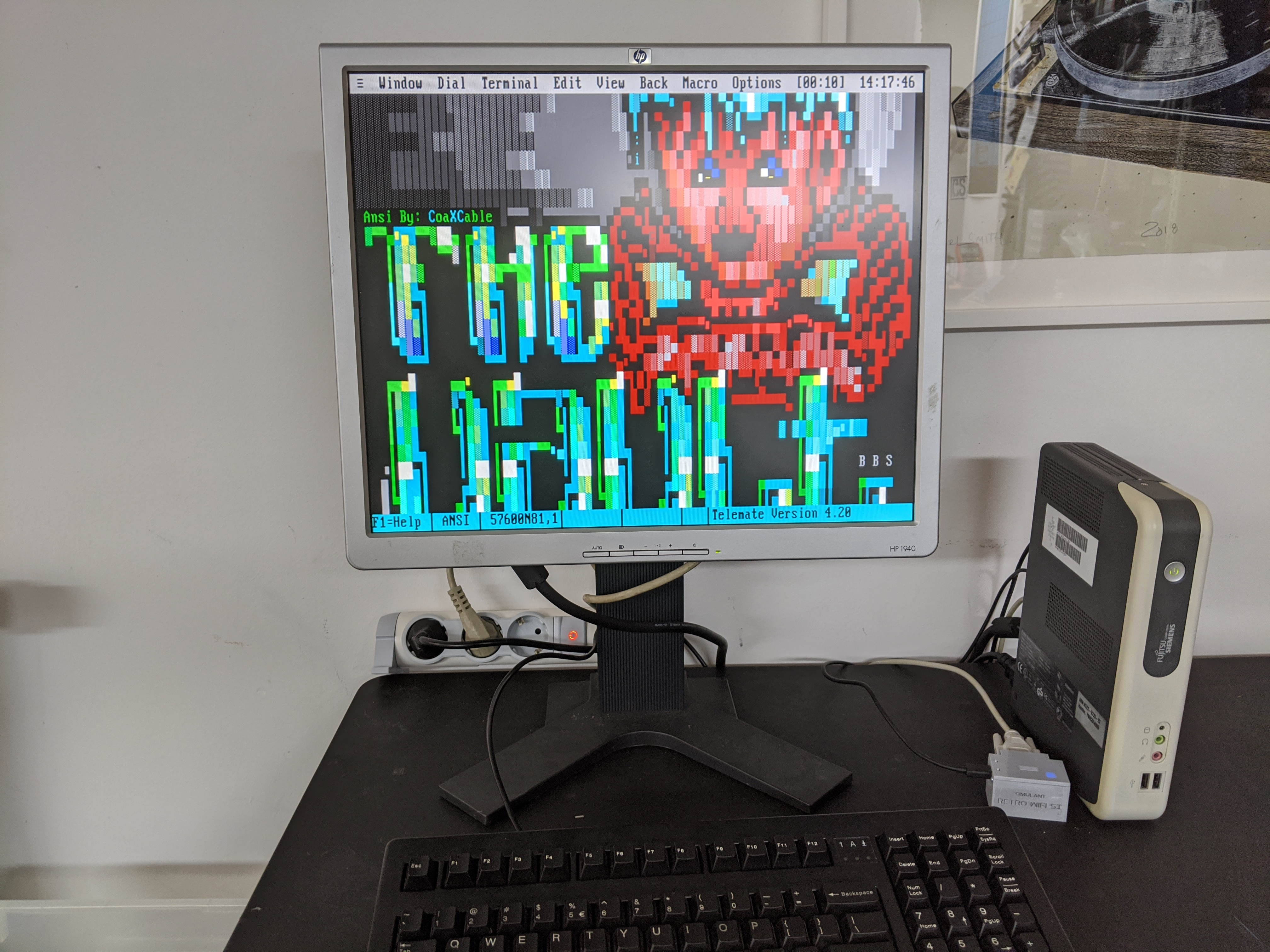

Recently, I wanted to recreate the experience of calling into BBSes, motivated by a fellow retrocomputing enthusiast who regularily tweeted screenshots of his nighttime BBS strawls, using 8 bit micros as his terminal. I decided that I would want to use a DOS based system as I never owned a real DOS machine before. Also, DOS terminal emulators should be compatible with many contemporary systems due to the ANSI terminal emulation.

I got myself a FSC Futro S200, which is a thin client based on the Transmeta Crusoe CPU. It is a sleek, fanless box, has a serial port and was specifically announced as supporting DOS on eBay. To connect to the Internet, I bought a Simulant WiFi SI “modem” - This is a small system based on the popular ESP8266 WiFi microcontroller that behaves like a modem on its serial port, but establishes TCP connections over WiFi instead of modulating and demodulating audio signals sent over the phone line. It uses the open source software Zimodem as its firmware. As operating system, I use FreeDOS, a convenient and capable replacement for MS-DOS. I tried a bunch of different terminal emulators and settled for Telemate 4.20.

On Timing and the Escape Character

When I started visiting BBSes with my new gear, I found that some systems would need me to use the arrow keys for navigation, but that these keys did not work as expected. Instead of performing the intended function, they’d be interpreted as if I had pressed the Escape key followed by some other characters.

To understand what’s going on, it helps to know what an ANSI terminal

sends when the arrow or function keys are pressed. Each of these keys

sends a specific sequence of multiple characters, starting with what

in ANSI parlor is called the “Control Sequence Introducer” (CSI): The

Escape control followed by the [ character. For the arrow keys, the

CSI is followed by A, B, C or D for the actual direction.

In many systems, the Escape key alone has some specific function, and it is unfortunate that Escape is also used as part of the CSI: In order for a system to distinguish between the Escape key and one of the function and arrow keys, all it can do is rely on the timing between the Escape and any characters that follow. If Escape is “immediately” followed by another character, it is interpreted as control sequence. If the Escape character is followed by a “pause”, it is interpreted as as the Escape key.

Zimodem, Sending Data and a Simple IP Stack

As I mentioned, my WiFi “modem” is based on the Zimodem software which in turn makes use of the IP stack that is part of the Arduino board support package for the ESP8266 CPU. Let’s have a look what packets are sent out when an arrow key is pressed on the terminal (tcpdump output slightly edited for legibility):

17:44:09.226048 IP modem.49154 > server.telnet: Flags [P.], seq 2:3, ack 181, win 2002, length 1

0x0020: 5018 07d2 5bf6 0000 1b00 0000 0000 P...[.........

17:44:09.273343 IP server.telnet > modem.49154: Flags [.], ack 3, win 29200, length 0

17:44:09.275704 IP modem.49154 > server.telnet: Flags [P.], seq 3:5, ack 181, win 2002, length 2

0x0020: 5018 07d2 1bb3 0000 5b41 0000 0000 P.......[A....

17:44:09.275769 IP server.telnet > modem.49154: Flags [.], ack 5, win 29200, length 0

We can see that four packets are required to get the arrow key sent to

and confirmed by the server. The first packet (length 1) contains

just the escape key at offset 0x0028. The third packet (length 2)

contains the two characters [ and A. Now, this would not be a

problem in general, as the packet structure is not seen by the BBS

software. It is a problem, though, that the second packet is only

sent out after the first one has been confirmed. As can be observed

in the time stamps, this causes a gap of 50 milliseconds between

sending the initial packet with the Escape character and the rest of

the control sequence.

The solution to the problem is to buffer the data received on the serial port for a little while to make sure that the complete control sequence is collected before it is sent out as one TCP packet. I’ve implemented a fix, so if you want to follow my path, you can now use arrow keys even if you are connecting to far-away BBSes.

Flashbacks

In the 1970ies, proprietary systems were everywhere and every computer vendor had their own line of terminals, incompatible to anything else. The ANSI X3.64 / ECMA-48 Standard set out to unify the mess of incompatible terminal control sequences, and if that had been adopted widely and quickly, we’d probably no Escape key on any keyboard. As many terminal vendors already had sold large numbers of terminals having Escape keys, the incompatibility between Escape as a standalone key and as part of a control sequence was there to stay and be dealt with.

In the 1980ies, properly handling Escape and function keys was not an all-that-easy thing to do because having to deal with real-time problems of this kind in application programs was difficult and error prone. Libraries like the infamous curses abstracted the problem away from applications. Still, it would probably have been wiser if the standardization bodies had chosen a different character to introduce a control sequence.